Tragedy in the Amazon

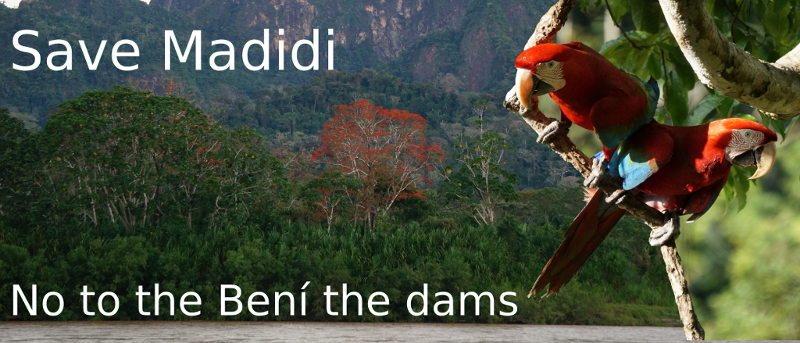

The Tambopata-Madidi area on the foothills of the Andes is one if the last areas of Amazonian forest that is relatively untouched by man. It contains 42000km2 of national parks, ranging from Tambopata in Peru to Madidi and Pilón Lajas in Bolivia. It is home to two important tributaries of the Amazon river and an incredible biodiversity with both montane and lowland tropical forest, harbouring over 10% of the world’s bird species, and possibly the most biodiverse place in the world. Around 15000-30000 people divided among three different indigenous peoples call it their home, with an interesting cultural diversity, bridging the Highland people for which Peru and Bolivia are famous to the lowland Amazonian tribes.

The Tambopata-Madidi area on the foothills of the Andes is one if the last areas of Amazonian forest that is relatively untouched by man. It contains 42000km2 of national parks, ranging from Tambopata in Peru to Madidi and Pilón Lajas in Bolivia. It is home to two important tributaries of the Amazon river and an incredible biodiversity with both montane and lowland tropical forest, harbouring over 10% of the world’s bird species, and possibly the most biodiverse place in the world. Around 15000-30000 people divided among three different indigenous peoples call it their home, with an interesting cultural diversity, bridging the Highland people for which Peru and Bolivia are famous to the lowland Amazonian tribes.

As a gateway to this biological and cultural diversity, Rurrenabaque in Bolivia has attracted many visitors from all over the world for many years and has been a thriving eco-tourism destination with around 30000 tourists visiting the area in 2005 alone. Now, all this is threatened in the name of “progress”. A badly planned bridge over the Rio Beni followed by a large road through the park and other short-sighted economical developments have already had a negative impact on the tourism in the area, but now president Evo Morales is planing to build two hydroelectric dams in the river Beni, two giant artificial lakes which will inundate around 2000km2, including substantial parts of the Madidi and Pilón Lajas national parks. But besides inundating primary forest and killing an enormous diversity of flora and fauna, giant dams like this have much wider ranging ecological impacts. The dams, cutting off one of the muddiest tributaries to the Amazon, will also prevent nutrients and minerals to be transported downstream, not only causing large ecological impacts on the remaining forests in Brazil but also causing eutrophication of the lake with bad water quality, low biodiversity and a breeding ground for parasites as consequences. The dams further downstream in Brazil have also proven to Bolivia that these mega dams elevate the risk of flooding upstream caused by el niño/la niña and influence migratory behaviour of fish along the whole Amazon River. And of course such a massive deforestation will have an impact on both the local climate and will be another nail in the coffin of human induced climate change.

Also from an economical standpoint these lakes are questionable. The electricity is generated purely to sell to Brazil. Their places with high demand are on the other side of Bolivia, incurring high transportation costs. And a market with only one buyer for your product allows the buyer to push the price down. This has happened before in Paraguay where Brazil buys electricity from a giant hydroelectric dam below cost price. The returns on investment are therefore very likely much worse than projected by the government. For this reason a number hydroelectric projects in neighbouring countries have been canceled. And even when accepting the expected income, looking at the sheer size of the lake (which multiple examples have shown is usually grossly underestimated initially) in comparison with the projected income from the electricity, it is a bad use of the surface area. Besides there being viable smaller scale hydroelectric alternatives, many alternative low-cost and sustainable sources of income have already been realised and can be expanded upon. The thriving eco-tourism in the area and the examples of sustainable agriculture projects are just two examples. The lakes will irreversibly destroy the eco-tourism and agricultural activities. With Rurrenabaque being one of the two major tourism destinations in Bolivia, the economical consequences will be wide ranging and not only limited to Rurrenabaque.

Another tragedy is the cultural impact. Multiple indigenous people (Tsimane, Mosetén and Tacana), some of which still live in isolation in their traditional culture by choice, will loose their territory, livelihood and homes. This is not only a tragedy but even illegal under Bolivian law, where indigenous tribes have a high level of autonomy over their territory. Due to the geology of the land, the indigenous people live in sparsely populated but relatively small areas. A relocation will force a complete people to live in exile and quickly loose their culture.

These cultural, ecological and economical tragedies can and should be prevented. Foreigners can’t do much to convince the president of Bolivia, but I hope that with enough interest and attention abroad, enough Bolivian people will realise that this project is an all round bad idea and will listen to their countrymen and -women who are working hard and not without danger, to convince their politicians. If you want to help, please sign the petition and spread the word on Facebook or in any other way you can. A great group where many Bolivian people who want to stop the project are a member of can be found on Facebook.

Sources:

- https://bolivia.wcs.org/en-us/Landscapes/Madidi-Tambopata.aspx

- http://drobisonbolivia.blogspot.com/2016/09/represas-en-el-bala-y-chepete-pura.html?spref=fb&m=1

- https://es.scribd.com/mobile/document/274405657/EL-BALA-LA-GRAN-DEVASTACION-EN-LA-AMAZONIA-BOLIVIANA

- http://porlatierra.org/novedades/post/127

- http://www.lostiempos.com/tendencias/interesante/20160814/crisis-rurrenabaque-pesadilla-china

- http://tur.sb-10.org/doc/6649/index.html

- http://dice.missouri.edu/docs/south-america-other/Tacana.pdf

- http://dice.missouri.edu/docs/south-america-other/Tacana_2.pdf

- http://dice.missouri.edu/docs/south-america-other/Tsimane.pdf